Designing and constructing sustainable buildings has become a mainstream expectation of most building owners. Whether for reduced energy costs, higher returns on investment, or as an organizational philosophy, “green” building solutions are in demand. Perhaps the best known and most often cited program to achieve these goals is the US Green Building Council’s (USGBC’s) LEED® rating system. While some may think that green buildings are more complicated and costly to build, that is not actually the case. This is especially true when metal building materials are used. In fact, metal buildings are an ideal and economical way to pursue sustainability goals and LEED certification. How? We break it down as follows:

The LEED® Program

The LEED program has been in use since 1998 and is now used worldwide. It is a voluntary, point-based rating system that allows for independent review and certification at different levels. These levels include Certified (40-49 points), Silver (50-59 points), Gold (60-79 points), or Platinum (80 or more points). Since it allows for choices in which points are pursued, innovation and flexibility are entirely possible as long as specific performance criteria are met. It also encourages collaborative and integrative design, construction and operation of the building.

Points are organized into six basic categories, many of which can be addressed through metal building design and construction, as summarized below.

- Location and Transportation: Metal buildings can be manufactured and delivered to virtually any location. That means they can support LEED criteria for being located near neighborhoods with diverse uses, available mass transit, bicycle trails, or other sustainable amenities. Metal building parking areas can also be designed to promote sustainable practices for green vehicles and reduced pavement. This all contributes toward obtaining LEED eligibility.

- Sustainable Sites: Adding a building to any site will certainly impact the natural environment already there. Delivering portions of a pre-engineered metal building package in a sequence to arrive as needed means that the staging area on-site can be minimized—reducing site impacts. Additionally, using a “cool metal roof” has been shown to reduce “heat island” effects on the surrounding site and also qualify for LEED.

- Water Efficiency: Any design that reduces or eliminates the need for irrigation of plantings and other outdoor water uses is preferred. Incorporating metal roofing with gutters and downspouts, as is commonly done on metal buildings, allows opportunities to capture rainwater for irrigation or other uses. It also helps control water run-off from the roof and assists with good storm water control.

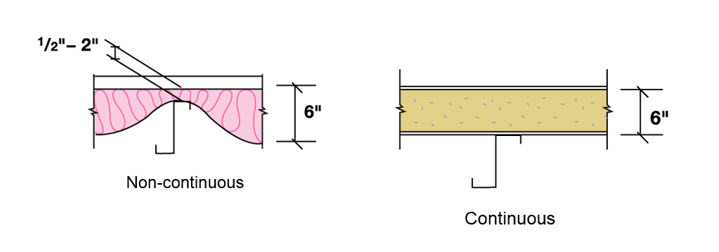

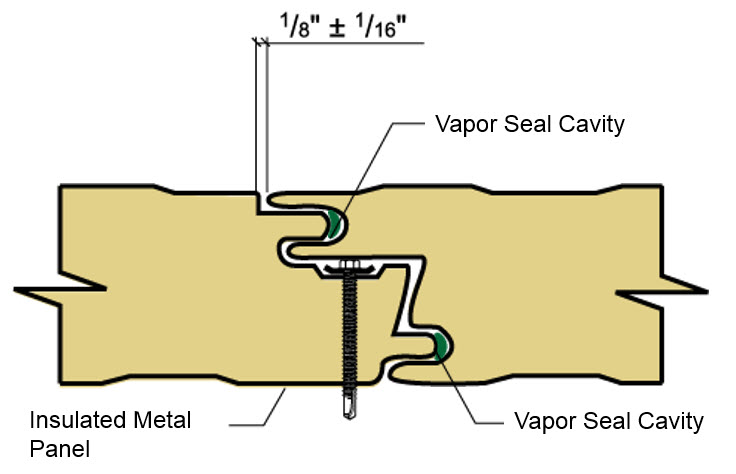

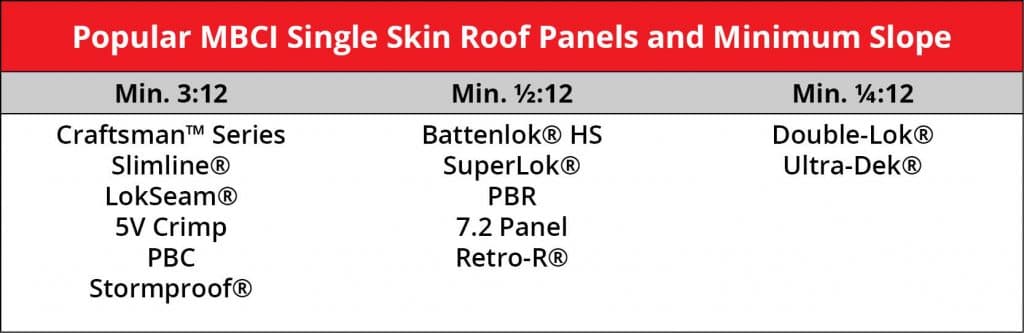

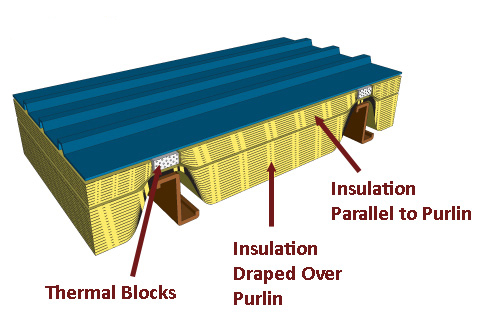

- Energy and Atmosphere: Metal buildings can truly shine in this category. Creating a well-insulated and air-sealed building enclosure is the most important and cost-effective step in creating an energy conserving building. A variety of insulation methods for metal building roof and wall systems are used to achieve this. Typically, metal building construction uses one or more layers of fiberglass insulation and liners combined with sealant and air barriers. Alternatively, insulated metal panels (IMPs) provide all of these layers in a single manufactured sandwich panel with impressive performance. Windows, skylights and translucent roof panels can provide natural daylight, allowing electric lighting to be dimmed or turned off. For buildings seeking to generate their own electricity, standing-seam metal roofing provides an ideal opportunity for the simplified installation of solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. Metal roofs generally provide a sustainable service life in excess of 40 years. This means they can outlast the PV array, thus avoiding costly roof replacements during most PV array lifespans.

- Materials and Resources: Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) are recognized by LEED as the most effective means to holistically assess the impacts that materials and processes have on the environment and on people. Fortunately, the Metal Building Manufacturer’s Association (MBMA) has collaborated with the Athena Sustainable Materials Institute and UL Environment to develop an industry-wide life cycle assessment report. There is also an Athena Impact Estimator that can help with providing LEED documentation. Metal buildings support exceptional environmental performance through the significant use of recycled steel and the reduced need for energy intensive concrete due to lighter weight buildings.

- Indoor Environmental Quality: Most people spend much more time indoors than outside, which impacts human health. Therefore, LEED promotes or requires using materials that don’t contain or emit harmful substances. It also promotes design options for natural daylight, exterior views and acoustical control to promote psychological and emotional well-being. Metal buildings are routinely designed to readily incorporate components that help achieve these indoor qualities.

In addition, some LEED points are available for demonstrating innovation and addressing priorities within a geographic region.

Considering the qualities listed above, metal buildings clearly provide a prime opportunity to pursue LEED certification at any level. To find out more about the LEED rating system, visit https://new.usgbc.org/leed. To find out more about successfully designing and constructing metal buildings pursuing LEED certification, contact your local MBCI representative.