Panelized metal exteriors have joints. It’s just a rule of best-practice design. Yet these joints are seen by some as interruptions in the façade or roof, when in fact they are connections — the opposite, one can argue, of the word “interruption” that suggests a discontinuity.

In fact, engineered metal panel systems offer arguably the best possible continuous exterior system. Not only are they properly applied exterior to the building structure—outboard of columns, joists and girts—but they are also designed to ensure an unbroken chain of thermal control and barrier protection. Combined with controlled penetration assemblies as well as windows, doors and skylights that are engineered as part of the façade and roof system, the insulated metal panel (IMP) products provide unequaled performance.

In fact, engineered metal panel systems offer arguably the best possible continuous exterior system. Not only are they properly applied exterior to the building structure—outboard of columns, joists and girts—but they are also designed to ensure an unbroken chain of thermal control and barrier protection. Combined with controlled penetration assemblies as well as windows, doors and skylights that are engineered as part of the façade and roof system, the insulated metal panel (IMP) products provide unequaled performance.

That’s the main reason that specialized facilities designed for maximum environmental barrier control are made of IMPs: refrigerated warehouses, R&D laboratories, air traffic control towers and MRI clinics, to name a few.

But any facility should benefit from the best performance possible with metal roofing and wall panels. Consider insulation shorthand for the code-mandated thermal barrier required for opaque wall areas in ASHRAE 90.1 and the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC). For a given climate zone, says Robert A. Zabcik, P.E., director of R&D with NCI Group, the project team can calculate the functional amount of insulation needed by using either the “Minimum Rated R-values” method or the “Maximum U-factor Assembly” calculation. For IMPs, teams use the Maximum U-factor Assembly, which can be tested using ASTM C1363.

With IMPs, the test shows thermal performance values up to R-8.515 and better per inch of panel thickness, meaning that a 2.5-inch-deep panel would easily meet the IECC and ASHRAE minimums.

With metal roofing panels and wall panels, a building team can achieve needed energy performance levels with this single-source enclosure, providing a continuous blanket of protection.

The same is true for air and moisture control. In a July 2015 paper by Building Science Corp., principal John Straube wrote, “Insulated metal panels can provide an exceptionally rigid, strong and air impermeable component of an air barrier system.” He noted that, “Air leakage condensation cannot occur within the body of the insulated metal panel, even if one of the metal skins is breached, because all materials are completely air impermeable and there are no voids to allow air flow.”

In terms of water control, Straube writes that IMPs have a continuous steel face that is a “high-performance, durable water control layer: water simply will not leak through steel, and cracks and holes will not form over time. The exterior location of the water barrier,” he adds, “offers some real advantages.”

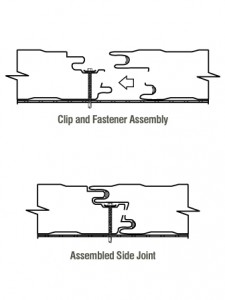

Connecting the panels at transitions, penetrations and panel joints is the key, of course. Straube notes that sealant, sheet metal, and sheet membranes are effective and commonly used to protect joints.

In my experience, these joint details are incredibly effective. They often outlast most other components of the building. Even more important, they help make IMPs better barriers that meet thermal, air and moisture performance needs. They help make metal panels one of the best choices of all.